BLOG

Using the Hierarchy of Controls to make sensible safety decisions

To create a safe working environment, employers are required to identify the main risks present within their organisation and the measures needed to manage them responsibly. This means carrying out a risk assessment and doing everything ‘reasonably practicable’ to protect people from harm.

Deciding on reasonably practicable solutions often causes confusion for employers, who will want to ensure that risks are being properly managed without being overly cautious and restrictive. Indeed, the HSE advocates that businesses should make sensible, proportionate decisions about what steps are necessary – but how can employers determine the most appropriate control measure?

That’s where the Hierarchy of Controls comes in.

What is the Hierarchy of Controls?

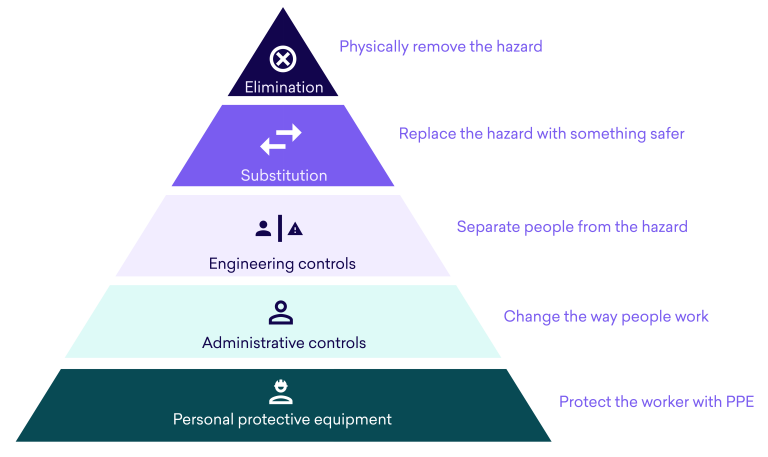

The Hierarchy of Controls provides a structured and consistent approach to the risk management process by ranking the different categories of control measures in the order in which employers should apply them.

In short, the hierarchy serves to help employers select the most effective controls to eliminate or reduce identified risks by having them consider these first. Only once employers have exhausted the control measures required at the top levels because they are not reasonably practicable should they proceed to the next level.

Whether assessing the adequacy of existing controls or introducing new ones, the Hierarchy of Controls should be kept in mind, as referring to it will help employers confirm that they are doing enough.

While there a number of different versions of the hierarchy, the following five control areas are recommended by WorkNest – in order of priority from most to least effective.

Do you need support?

Speak to us for an honest, no obligation chat on:

0345 226 8393 Lines are open 9am – 5pm

1. Elimination (most effective)

This is the first rung on the Hierarchy of Controls as, naturally, removing a hazard altogether is the most obvious and effective way to prevent harm.

Elimination occurs when a process or activity is abandoned because the associated risk is too high. An example could be eliminating a working at height risk by carrying out the work at ground level – the hazard is eliminated by moving what is being worked on to ground level.

Although the most efficacious control measure, elimination is also typically the most challenging to implement, as doing so can involve major overhauls in pre-existing workplace processes. It is therefore not always possible to go down this route, and it can be more practical (and cheaper) to eliminate hazards at the design or planning stage of a process, product or workplace.

Hazards can, however, be eliminated simply – examples include removing trip hazards on the floor or disposing of unwanted chemicals to eliminate the risks they create.

2. Substitution

If it isn’t reasonably practicable to eliminate the hazard, employers should seek to minimise the risks through substitution. This second most effective hazard control method involves replacing something hazardous with something that doesn’t produce a hazard or produces less of a hazard.

Substitution serves a similar purpose to elimination – it removes a hazard from the workplace or decreases the potential for that hazard to negatively affect employees. If a workplace process is still in its design or development phase, substitution can be an inexpensive method of managing a hazard.

There are many substitution examples such as using a better-guarded type of machine to make the same product, using asbestos substitutes, and using compressed air as a power source rather than electricity. Other examples include using a scourer, mild detergent and hot water instead of caustic cleaners, or using a cordless rather than electric drill if the power cord is in danger of being cut.

To be an effective control, care must be taken not to introduce additional hazards and risks as a result of the substitution.

3. Engineering controls

This third most effective means of risk control doesn’t eliminate the hazard, but rather isolates people from the hazard. An engineering control describes a physically-designed measure that again controls the hazard at its source – it requires physical changes to be made to the risk or situation, such as an adjustment or alteration to a machine or landscape.

Engineering controls can control the risk of exposure by isolating equipment through the use of enclosures, barriers or guards, for example, around moving parts of dangerous machinery. They can also insulate against any temperature or electrical hazard, or ventilate away any hazardous dust, fumes or gases via extractor fans and fume hoods.

Another recent example of an engineering control would be the Perspex screens many businesses erected to prevent the spread of COVID-19, which provided a physical barrier between people and the potential hazard.

While the capital cost of engineered controls tends to be higher than the less effective controls in the hierarchy, they may reduce future costs.

4. Administrative controls

Administrative controls involve changes and adaptations to the way people work. Measures involve developing work procedures that favour safe working practices. Administrative controls don’t remove hazards – instead they seek to minimise or prevent the hazard/risk through the design of safe(r) work systems.

Examples typically include rearranging or updating the steps in a job process – such as rotating workers to reduce their exposure time in a noisy area – or rotating staff through various job assignments so that they don’t develop repetitive motion injuries. Using machinery as an example, other administrative controls might include:

- Performing a daily check on the machinery to ensure it’s in good working order;

- Including training on how to use machinery safely;

- Creating better safety checklist processes; and

- Placing signage around machinery to warn of the hazard.

Sometimes the pattern of work can be changed so that people do things in a more natural way, for example considering whether workers are left or right-handed when removing and/or packing components, or encouraging office workers to take short breaks away from computer screens.

5. Personal protective equipment (least effective)

Finally, if all of the above measures don’t sufficiently control the risk to a reasonably practicable level, then the next step is to provide PPE to workers. PPE is the lowest and least effective control in the hierarchy, as if the equipment fails, workers are exposed to the hazard and the harm could be significant.

PPE involves wearing and relying on any type of personal safety equipment – such as safety glasses, hardhats, fire-retardant clothing, ear defenders and safety boots. Using PPE as a hazard control includes using it properly, as well as maintaining and caring for it properly.

Unfortunately, the use of PPE is counterintuitive – many people see it as the first line of safety defence, when in reality it should be considered only as a last resort or in addition to other measures.

Putting it into practice

In effect, the Hierarchy of Controls is a simple way of assessing and prioritising control measures so that you can take the most effective steps to keep your workforce safe.

The hierarchy should be used by starting with elimination. If this isn’t possible, then look to find a substitute risk management process solution and so on.

As an example, say you need to open a package and this may involve using a bladed implement. According to the Hierarchy of Controls, you would first consider whether you can eliminate the need to use a blade to open the box. If you can’t, you would then consider:

Substitution: can you use a safer blade? If that’s not possible, consider…

Engineering controls: does a human need to do the cutting? If there’s no way around having a person to do the task, consider…

Administrative controls: can the worker use a safer cutting method? If that’s not an option, consider…

Providing PPE: could the worker use cut-resistant gloves?

Even if you have implemented some of the higher-level risk controls, you should still look for opportunities at the lower levels of the hierarchy for safety improvements.

Where applicable, a combination of controls should of course be used at any one time. The best way to think about the hierarchy is that the lowest controls or approaches should never be used exclusively to control risk. They should only be used to additionally control the risk. In the example above, you could have the worker use a safer blade and safer cutting method whilst also providing PPE.

Ideally, the approach to every risk should be to eliminate it completely. However, this may not be possible, with COVID-19 being the recent obvious example. There are often trade-offs in implementing any safety practice and each level of the hierarchy must be assessed on its own merit from a feasibility standpoint.

And as always, controls should be regularly reviewed to ensure they remain adequate and in place.

Related Content

Meet your duties confidently with WorkNest

At WorkNest, we understand that employers want to take health and safety seriously. We also understand that you have a business to run.

Our fixed-fee service gives you access to sensible, proportionate advice from your own dedicated Health & Safety specialist, who will help you to take a pragmatic, proactive approach to risk management and identify practical solutions to your health and safety challenges. Through a combination of consultant support, annual audits and simple, secure software, we’ll give you the confidence that you’re taking the necessary steps to protect your business and your people from the consequences of non-compliance.

To find out more, call 0345 226 8393 or request your free consultation using the button below.