Resources

All the latest insights, news and resources

Free webinar | 26 February, 2.00pm

Getting Inspection Ready for 2026 | practical steps to protect your business

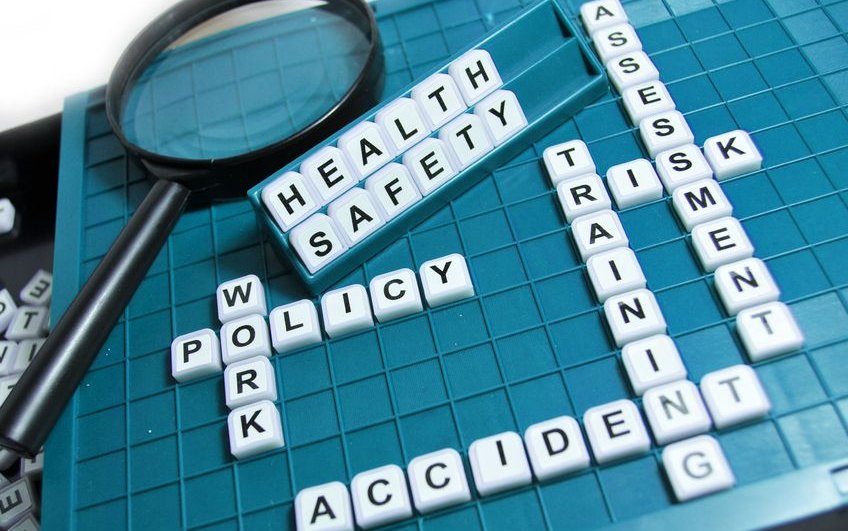

68% of UK businesses are likely to fail on the spot HSE inspections.

If an inspector walked onto your site tomorrow, would your systems, records and people stand up to scrutiny?

An HSE inspection can happen without warning. Failure to demonstrate effective health and safety management can lead to enforcement action, improvement or prohibition notices, investigations, prosecutions, fines, and serious disruption to your operations. In the most serious cases, poor compliance contributes to life-changing injuries, fatalities and lasting reputational damage.

Free webinar | 19 March, 9.30 am

Fire Safety in Education | from legal duties to practical protection

Free webinar | Available now

HR Made Simple for Small Businesses | what you need to know

Free webinar | Available now

Navigating Redundancies and Restructures in 2026 | legal updates and best practices

Events for employers

Be part of our upcoming in-person events, where industry experts share practical guidance, legal updates, and actionable insights to support your organisation. Network, learn, and stay ahead.

Personalise your content

20 Feb 2026

20 Feb 2026

20 Feb 2026

19 Feb 2026

10 Feb 2026

16 Feb 2026

09 Feb 2026

13 Jan 2026

23 Jan 2026

22 Jan 2026

22 Jan 2026

19 Jan 2026

16 Jan 2026

14 Jan 2026

12 Jan 2026

07 Jan 2025

06 Jan 2026

06 Jan 2026

05 Jan 2026

05 Jan 2026

05 Jan 2026

19 Dec 2025

18 Dec 2025

17 Dec 2025

12 Dec 2025

11 Nov 2025

10 Dec 2025

9 Dec 2025

04 Dec 2025

01 Dec 2025

27 Nov 2025

27 Nov 2025

26 Nov 2025

25 Nov 2025

21 Nov 2025

14 Nov 2025

13 Nov 2025

16 Oct 2025

12 Nov 2025

11 Nov 2025

07 Nov 2025

07 Nov 2025

03 Nov 2025

29 Oct 2025

22 Oct 2025

20 Oct 2025

17 Oct 2025

16 Oct 2025

14 Oct 2025

10 October 2025

9 Oct 2025

09 Oct 2025

06 Oct 2025

30 Sep 2025

25 Sept 2025

25 Sep 2025

25 Sep 2025

24 Sep 2025

29 Sep 2025

16 Sep 2025

12 Sep 2025

11 Sep 2025

10 Sep 2025

04 Sep 2025

02 Sep 2025

02 Sep 2025

29 Aug 2025

28 Aug 2025

27 Aug 2025

27 Aug 2025

26 Aug 2025

22 Aug 2025

21 Aug 2025

20 Aug 2025

19 Aug 2025

19 Aug 2025

14 Aug 2025

12 Aug 2025

12 Aug 2025

08 Aug 2025

08 Aug 2025

07 Aug 2025

05 Aug 2025

31 Jul 2025

31 Jul 2025

30 Jul 2025

17 Jul 2025

14 Jul 2025

14 Jul 2025

11 Jul 2025

10 Jul 2025

09 Jul 2025

05 Jul 2025

04 Jul 2025

03 Jul 2025

26 Jun 2025

26 Jun 2025

26 Jun 2025

25 Jun 2025

24 Jun 2025

24 Jun 2025

23 Jun 2025

18 Jun 2025

13 Jun 2025

25 Jan 2024

25 Jan 2024

12 Jun 2025

12 Jun 2025

12 Jun 2025

12 Jun 2025

11 Jun 2025

10 Jun 2025

09 Jun 2025

29 May 2025

29 May 2025

28 May 2025

23 May 2025

23 May 2025

22 May 2025

21 May 2025

21 May 2025

19 May 2025

14 May 2025

14 May 2025

14 May 2025

13 May 2025

12 May 2025

08 May 2025

07 May 2025

30 Apr 2025

29 Apr 2025

25 Apr 2025

23 Apr 2025

23 Apr 2025

22 Apr 2025

22 April 2025

22 Apr 2025

15 Apr 2025

10 Apr 2025

09 Apr 2025

07 Apr 2025

03 Apr 2025

31 Mar 2025

27 Mar 2025

25 Mar 2025

20 Mar 2025

19 Mar 2025

19 Mar 2025

18 Mar 2025

14 Mar 2025

14 Mar 2025

14 Mar 2025

12 Mar 2025

12 Mar 2025

12 Mar 2025

11 Mar 2025

28 Feb 2025

27 Feb 2025

26 Feb 2025

25 Feb 2025

21 Feb 2025

25 Feb 2025

19 Feb 2025

18 Feb 2025

17 Feb 2025

13 Feb 2025

13 Feb 2025

06 Feb 2025

30 Jan 2025

28 Jan 2025

24 Jan 2025

16 Jan 2025

20 Jan 2025

17 Jan 2024

10 Jan 2024

10 January 2025

07 Jan 2025

23 Dec 2024

20 Dec 2024

13 Dec 2024

12 Dec 2024

09 Dec 2024

09 Dec 2024

05 Dec 2024

02 Dec 2024

28 Nov 2024

27 Nov 2024

26 Nov 2024

25 Nov 2024

21 Nov 2024

19 Nov 2024

20 Nov 2024

18 Nov 2024

18 Nov 2024

14 Nov 2024

13 Nov 2024

12 Nov 2024

07 Nov 2024

05 Nov 2024

01 Nov 2024

30 Oct 2024

29 Oct 2024

25 Oct 2024

24 Oct 2024

24 Oct 2024

21 Oct 2024

18 Oct 2024

15 Oct 2024

10 Oct 2024

10 Oct 2024

27 Sep 2024

26 Sep 2024

26 Sep 2024

26 Sep 2024

20 Sep 2024

19 Sep 2024

17 Sep 2024

12 Sep 2024

10 Sep 2024

09 Sep 2024

09 Sep 2024

09 Sep 2024

05 Sep 2024

05 Sep 2024

05 Sep 2024

03 Sep 2024

02 Sep 2024

02 Sep 2024

02 Sep 2024

29 Aug 2024

27 Aug 2024

21 Aug 2024

8 Aug 2024

16 Aug 2024

15 Aug 2024

07 Aug 2024

07 Aug 2024

07 Aug 2024

02 Aug 2024

01 Aug 2024

29 Jul 2024

25 Jul 2024

19 Jul 2024

19 Jul 2024

18 Jul 2024

18 Jul 2024

12 Jul 2024

12 Jul 2024

12 Jul 2024

09 Jul 2024

09 Jul 2024

05 Jul 2024

03 Jul 2024

01 Jul 2024

01 Jul 2024

28 Jun 2024

28 Jun 2024

28 Jun 2024

26 Jun 2024

18 Jun 2024

17 Jun 2024

13 Jun 2024

10 Jun 2024

10 Jun 2024

10 Jun 2024

05 Jun 2024

05 Jun 2024

05 Jun 2024

03 June 2024

03 Jun 2024

29 May 2024

29 May 2024

24 May 2024

24 May 2024

23 May 2024

17 May 2024

17 May 2024

16 May 2024

28 May 2023

23 May 2023

15 May 2023

10 May 2023

29 Apr 2024

25 Apr 2024

22 Apr 2024

18 Apr 2024

17 Apr 2024

14 Apr 2024

16 Apr 2024

12 Apr 2024

10 Apr 2024

04 Apr 2024

21 Mar 2024

20 Mar 2024

29 Feb 2024

29 Feb 2024

28 Feb 2024

28 Feb 2024

28 Feb 2024

28 Feb 2024

28 Feb 2024

27 Feb 2024

22 Feb 2024

22 Feb 2024

20 Feb 2024

15 Feb 2024

14 Feb 2024

13 Feb 2024

12 Feb 2024

8 Feb 2024

31 Jan 2024

29 Jan 2024

25 Jan 2024

25 Jan 2024

24 Jan 2024

23 Jan 2024

22 Jan 2024

22 Jan 2024

18 Jan 2024

15 Jan 2024

02 Jan 2024

15 Dec 2023

15 Dec 2023

07 Dec 2023

30 Nov 2023

29 Nov 2023

27 Nov 2023

27 Nov 2023

24 Nov 2023

22 Nov 2023

17 Nov 23

17 Nov 2023

15 Nov 2023

13 Nov 2023

09 Nov 2023

01 Nov 2023

25 Oct 2023

23 Oct 2023

19 Oct 2023

13 Oct 2023

09 Oct 2023

05 Oct 2023

04 Oct 2023

02 Oct 2023

7 minutes 10 seconds

2 minutes 26 seconds

3 minutes 29 seconds

3 minutes 28 seconds

3 minutes 17 seconds

23 seconds

3 minutes

3 minutes 10 seconds

28 Sep 2023

21 Sep 2023

14 Sep 2023

13 Sep 2023

01 Sep 2023

31 Aug 2023

24 Aug 2023

17 Aug 2023

11 Aug 2023

03 Aug 2023

28 Jul 2023

28 Jul 2023

26 Jul 2023

17 Jul 2023

17 Jul 2023

14 Jul 2023

06 Jul 2023

29 June 2023

27 Jun 2023

14 Jun 2023

14 Jun 2023

09 Jun 2023

09 Jun 2023

06 Jun 2023

30 May 2023

19 May 2023

17 May 2023

12 May 2023

22 June

20 June

15 June

13 June

08 June

06 June 2023 - Morning Session

27 April 2023

26 Apr 2023

20 April 2023

06 Apr 2022

23 Mar 2023

23 Mar 2023

22 Mar 2023

14 Mar 2023

30 Mar 2023

21 Mar 2023 - Afternoon Session

22 Mar 2023 - Afternoon Session

28 Feb 2023

24 Feb 2023

24 Feb 2023

23 Feb 2023

22 Feb 2023

22 Feb 2023

17 Feb 2023

17 Feb 2023

17 Feb 2023

17 Feb 2023

22 Mar 2023

21 Mar 2023

16 Mar 2023

14 Mar 2023

07 Mar 2023

02 Mar 2023

09 Feb 2023

30 Jan 2023

02 Feb 2023

30 Jan 2023

27 Jan 2023

26 Jan 2023

24 Jan 2023

13 Jan 2023

10 Jan 2023

09 Jan 2023

04 Jan 2023

04 Jan 2023

04 Jan 2023

03 Jan 2023

05 Dec 2022

23 Nov 2022

17 Nov 2022

14 Nov 2022

07 Nov 2022

05 Nov 2022

02 Nov 2022

28 Oct 2022

24 Oct 2022

20 Oct 2022

14 Oct 2022

07 Oct 2022

9 & 10 Nov 2022

05 Oct 2022

04 Oct 2022

27 Sep 2022

21 Sep 2022

08 Sep 2022

08 Sep 2022

07 Sep 2022

30 Aug 2022

18 August 2022

18 Aug 2022

11 Aug 2023

11 Aug 2022

11 Aug 2022

08 Aug 2022

03 Aug 2022

01 Aug 2022

27 Jul 2022

27 Jul 2022

27 Jul 2022

20 Jul 2022

20 Jul 2022

19 Jul 2022

15 Jul 2022

15 Jul 2022

15 Jul 2022

15 Jul 2022

14 Jul 2022

14 Jul 2022

13 Jul 2022

12 Jul 2022

08 Jul 2022

30 Jun 2022

30 Jun 2022

28 Jun 2022

24 Jun 2022

10 Jun 2022

08 Jun 2022

07 Jun 2022

06 Jun 2022

30 May 2022

26 May 2022

25 May 2022

19 May 2022

18 May 2022

18 May 2022

16 May 2022

12 May 2022

06 May 2022

05 May 2022

04 May 2022

28 Apr 2022

28 Apr 2022

28 Apr 2022

21 Apr 2022

15 Apr 2022

13 Apr 2022

11 Apr 2022

11 Apr 2022

11 Apr 2022

11 Apr 2022

11 Apr 2022

11 Apr 2022

11 Apr 2022

11 Apr 2022

11 Apr 2022

11 Apr 2022

11 Apr 2022

11 Apr 2022

07 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

04 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

05 Apr 2022

04 Feb 2022

01 Apr 2022

31 Mar 2022

29 Mar 2022

23 Mar 2022

17 Mar 2022

16 Mar 2022

14 Mar 2022

11 Mar 2022

12 Mar 2022

09 Mar 2022

09 Mar 2022

08 Mar 2022

04 Mar 2022

02 Feb 2022

22 Feb 2022

22 Feb 2022

21 Feb 2022

22 Feb 2022

16 Feb 2022

15 Feb 2022

14 Feb 2022

14 Feb 2022

11 Feb 2022

10 Feb 2022

09 Feb 2022

08 Feb 2022

08 Feb 2022

07 Feb 2022

07 Feb 2022

04 Feb 2022

03 Feb 2022

01 Feb 2022

01 Feb 2022

01 Feb 2022

01 Feb 2022

26 Jan 2022

25, 26 and 27 Jan 2022

24 Jan 2022

24 Jan 2022

31 Jan 2022

21 Jan 2022

17 Jan 2022

13 Jan 2022

12 Jan 2022

11 Jan 2022

10 Jan 2022

07 Jan 2022

4 Jan 2022

24 Dec 2021

22 Dec 2021

22 Dec 2021

21 Dec 2021

16 Dec 2021

16 Dec 2021

15 Dec 2021

14 Dec 2021

14 Dec 2021

14 Dec 2021

14 Dec 2021

14 Dec 2021

14 Dec 2021

13 Dec 2021

10 Dec 2021

09 Dec 2021

09 Dec 2021

07 Dec 2021

06 Dec 2021

01 Dec 2021

01 Dec 2021

01 Dec 2021

25 Nov 2021

25 Nov 2021

22 Nov 2021

22 Nov 2021

22 Nov 2021

17 Nov 2021

17 Nov 2021

16 Nov 2021

12 Nov 2021

11 Nov 2021

09 Nov 2021

02 Nov 2021

01 Nov 2021

01 Nov 2021

29 Oct 2021

28 Oct 2021

22 Oct 2021

20 Oct 2021

20 Oct 2021

20 Oct 2021

15 Oct 2021

04 Oct 2021

01 Oct 2021

01 Oct 2021

01 Oct 2021

28 Sep 2021

24 Sep 2021

21 Sep 2021

20 Sep 2021

15 Sep 2021

14 Sep 2021

13 Sep 2021

09 Sep 2021

07 Sep 2021

02 Sep 2021

01 Sep 2021

01 Sep 2021

31 Aug 2021

26 Aug 2021

23 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

18 Aug 2021

17 Aug 2021

17 Aug 2021

12 Aug 2021

11 Aug 2021

11 Aug 2021

11 Aug 2021

09 Aug 2021

09 Aug 2021

05 Aug 2021

04 Aug 2021

03 Aug 2021

03 Aug 2021

30 Jul 2021

23 Jul 2021

22 Jul 2021

22 Jul 2021

22 Jul 2021

21 Jul 2021

20 Jul 2021

20 Jul 2021

20 Jul 2021

16 Jul 2021

16 Jul 2021

15 Jul 2021

14 Jul 2021

13 Jul 2021

13 Jul 2021

08 Jul 2021

08 Jul 2021

05 Jul 2021

30 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

2021

28 Jun 2021

26 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

22 Jun 2021

21 Jun 2021

18 Jun 2021

17 Jun 2021

16 Jun 2021

16 Jun 2021

15 Jun 2021

11 Jun 2021

11 Jun 2021

09 Jun 2021

07 Jun 2021

07 Jun 2021

07 Jun 2021

02 Jun 2021

02 Jun 2021

01 Jun 2021

27 May 2021

21 May 2021

18 May 2021

18 May 2021

14 May 2021

13 May 2021

12 May 2021

12 May 2021

11 May 2021

07 May 2021

06 May 2021

05 May 2021

04 May 2021

29 Apr 2021

29 Apr 2021

28 Apr 2021

27 Apr 2021

22 Apr 2021

20 Apr 2021

14 Apr 2021

14 Apr 2021

08 Apr 2021

08 Apr 2021

06 Apr 2021

30 Mar 2021

24 March 2021

19 Mar 2021

18 Mar 2021

18 March 2021

15 Mar 2021

4 Mar 2021

4 Mar 2021

03 Mar 2021

03 Mar 2021

25 Feb 2021

03 Mar 2021

03 Mar 2021

02 Mar 2021

01 Mar 2021

25 Feb 2021

24 Feb 2021

23 Feb 2021

19 Feb 2021

18 Feb 2021

18 Feb 2021

18 Feb 2021

17 Feb 2021

16 Feb 2021

15 Feb 2021

09 Feb 2021

09 Feb 2021

08 Feb 2021

03 Feb 2021

03 Feb 2021

01 Feb 2021

01 Feb 2021

28 Jan 2021

27 Jan 2021

27 Jan 2021

27 Jan 2021

26 Jan 2021

20 Jan 2021

19 Jan 2021

18 Jan 2021

18 Jan 2021

14 Jan 2021

13 Jan 2021

11 Jan 2021

07 Jan 2021

07 Jan 2021

06 Jan 2021

05 Jan 2021

05 Jan 2021

04 Jan 2021

04 Jan 2021

24 Dec 2020

21 Dec 2020

21 Dec 2020

17 Dec 2020

16 Dec 2020

11 Dec 2020

10 Dec 2020

07 Nov 2020

03 Nov 2020

02 Dec 2020

30 Nov 2020

30 Nov 2020

25 Nov 2020

24 Nov 2020

24 Nov 2020

19 Nov 2020

18 Nov 2020

16 Nov 2020

13 Nov 2020

12 Nov 2020

10 Nov 2020

10 Nov 2020

06 Nov 2020

06 Nov 2020

05 Nov 2020

04 Nov 2020

04 Nov 2020

03 Nov 2020

03 Nov 2020

29 Oct 2020

29 Oct 2020

22 Oct 2020

21 Oct 2020

21 Oct 2020

21 Oct 2020

19 Oct 2020

16 Oct 2020

16 Oct 2020

16 Oct 2020

13 Oct 2020

13 Oct 2020

12 Oct 2020

06 Oct 2020

02 Oct 2020

01 Oct 2020

29 Sep 2020

25 Sep 2020

25 Sep 2020

24 Sep 2020

20 Sep 2020

18 Sep 2020

18 Sep 2020

17 Sept 2020

15 Sep 2020

10 Sept 2020

10 Sep 2020

09 Sep 2020

04 Sep 2020

03 Sept 2020

01 Sep 2020

27 Aug 2020

24 Aug 2020

21 Aug 2020

19 Aug 2020

14 Aug 2020

14 Aug 2020

12 Aug 2020

10 Aug 2020

08 Aug 2020

03 Aug 2020

31 Jul 2020

30 Jul 2018

30 Jul 2020

30 July 2020

27 Jul 2020

24 July 2020

16 July 2020

22 Jul 2020

16 Jul 2020

14 Jul 2020

13 Jul 2020

12 Jul 2020

03 Jul 2020

01 Jul 2020

30 Jun 2020

24 Jun 2020

18 Jun 2020

11 Jun 2020

08 Jun 2020

03 Jun 2020

29 May 2020

28 May 2020

18 May 2020

11 May 2020

07 May 2020

06 May 2020

01 May 2020

30 Apr 2020

30 Apr 2020

30 Apr 2020

30 Apr 2020

28 Apr 2020

27 Apr 2020

23 Apr 2020

21 Apr 2020

20 Apr 2020

15 Apr 2020

09 Apr 2020

07 Apr 2020

07 Apr 2020

02 Apr 2020

02 Apr 2020

01 Apr 2020

01 Apr 2020

01 Apr 2020

31 Mar 2020

30 Mar 2020

26 Mar 2020

20 Mar 2020

12 Mar 2020

11 Mar 2020

10 Mar 2020

06 Mar 2020

05 Mar 2020

05 Mar 2020

04 Mar 2020

03 Mar 2020

28 Feb 2020

27 Feb 2020

27 Feb 2020

21 Feb 2020

20 Feb 2020

19 Feb 2020

18 Feb 2020

17 Feb 2020

17 Feb 2020

14 Feb 2020

14 Feb 2020

10 Feb 2020

10 Feb 2020

06 Feb 2020

06 Feb 2020

04 Feb 2020

03 Feb 2020

01 Feb 2020

27 Jan 2020

24 Jan 2020

23 Jan 2020

22 Jan 2019

22 Jan 2020

21 Jan 2020

19 Jan 2020

17 Jan 2020

16 Jan 2020

15 Jan 2020

13 Jan 2020

10 Jan 2020

08 Jan 2020

08 Jan 2020

07 Jan 2020

06 Jan 2020

01 Jan 2020

19 Dec 2020

12 Dec 2019

09 Dec 2019

01 Nov 2019

27 Oct 2019

07 Oct 2019

27 Sep 2019

13 Sep 2019

16 Aug 2019

09 Aug 2019

09 Aug 2019

15 Aug 2019

31 July 2019

24 July 2019

29 Oct 2020

18 Jul 2019

18 July 2019

04 Jul 2019

19 Jun 2019

17 Jun 2019

05 Jun 2019

22 May 2019

14 May 2019

01 May 2019

19 Apr 2019

22 Mar 2019

27 Sep 2018

13 Sep 2018

12 Sep 2019

28 Aug 2018

24 Aug 2018

18 Jun 2018

07 Jun 2018

07 Jun 2018

28 Mar 2018

19 Mar 2018

18 Feb 2018

07 Feb 2018

Jan 31 2018

07 Nov 2017

30 Oct 2017

13 Oct 2017

12 Sep 2017

12 May 2017

24 Apr 2017

13 Apr 2017

11 Apr 2021

17 Mar 2017

28 Nov 2016

07 Nov 2016